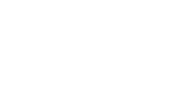

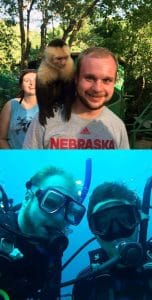

Adam Manglitz’s wildlife biology degree has been a ticket to exotic experiences. As a student at Hastings College, Manglitz ‘18 traveled to Honduras to scuba dive with sharks and hold a white-faced capuchin. After graduating, he moved to the Florida Keys, where he wrangled pelicans and rehabilitated raptors.

Recently, though, his degree brought him back to Nebraska for something a little more domestic: veterinary medicine.

This fall, Manglitz started his second year of the Professional Program of Veterinary Medicine, a partnership between Iowa State University and the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. The “2+2 program” sends students to study two years at UNL, then two years at ISU. They graduate with a Doctorate of Veterinary Medicine. Manglitz’s ultimate goal is to open his own veterinary practice—one that ties in some of his more adventurous animal experiences.

“I really enjoy dogs and cats, and I love working with them, but it can get a little boring if that’s all you see,” he said. “I’m focused on mixed practice, so I could also help exotic pets. And I’d really like to get to the point where I’d feel comfortable looking at any animal someone wants me to look at.”

This story originally appeared in the 2024 HC Today.

Cultivating interest in medicine

Manglitz said he never envisioned himself entering the medical field, be it animal or human. He studied wildlife biology as an undergrad because he liked ecology and biology, and wildlife biology combined those two topics well.

“The medical field was not on my radar. I don’t fully know what, but I just never thought it would be that interesting to me,” he said. “It wasn’t until I got more real-life experience working in Florida that I realized I might actually enjoy it.”

Manglitz moved to the Sunshine State in 2018 for a one-year internship with the Florida Keys Wild Bird Rehabilitation Center. He cared for the center’s “resident birds,” or those that were unable to be released back into the wild. Later, he was hired full-time as a hospital technician who helped care for sick or injured birds.

“I got to experience doing wing wraps for broken wings, and there was a lot of feeding baby birds that had been abandoned,” Manglitz said. “It’s really satisfying to see an injured bird that can’t walk slowly improve based on what you’re doing to it. It’s also rewarding to get to see it fly away once it’s fully recovered.”

Pelicans were some of the hospital’s most common patients. Oftentimes, the birds will get fish hooks caught in their throats. The hospital tech’s job involved finding injured pelicans and bringing them into the hospital, so the vets could remove the hooks. In one rare case, Manglitz helped capture a pelican that had swallowed a cellphone.

“I actually really miss catching pelicans,” Manglitz said. “I failed a lot of times to start, but eventually I got really good at it.”

The trick is to use fish to draw the bird toward the boardwalk, then quickly scoop it up with a net before it realizes what’s happening. Then, you secure it by holding both wings in one hand, and the mouth in the other.

“Certain species have the ability to hurt you, so you want to be careful,” Manglitz said. “For example, when working with raptors, the first thing you want to grab and get secured is their talons. A pelican’s beak can be dangerous, so that’s why you want to make sure it’s secure.”

The more birds he helped, the more his interest in animal medicine grew. He said it was gratifying to diagnose a sick bird, then nurse it back to health.

“I also found it really interesting to watch the veterinarian perform surgeries. It made me want to pursue more veterinary medicine,” Manglitz said. “I decided to apply for jobs at vet clinics to see if I liked working with domestic animals, as well.”

Developing more skills

In 2021, he returned to Nebraska and started working for the Veterinary Eye Specialists of Nebraska in Omaha, a specialty clinic that focuses on pet eye issues. His job as a vet assistant included monitoring pets under anesthesia, assisting with surgery, drawing blood and putting in catheters.

“A lot of people consider their pets as family members, so it can be scary and stressful when their animal needs to go to the vet,” Manglitz said. “It can be very gratifying to see an owner’s reaction to how you treat and help their pets.”

After building up some experience at the clinic, Manglitz decided to apply for vet school. The Professional Program of Veterinary Medicine is a highly competitive program open to Nebraska residents only, with spots for 25-30 students each year. It’s not uncommon for a student to apply two or three times before getting accepted, Manglitz said.

His first application earned him a spot as a “first alternate,” but no students dropped from the cohort to open a spot for him. His second application got him accepted in full.

“I tell the undergrads I’m working with not to get discouraged for not getting in. A lot of my classmates didn’t get in on their first try either,” Manglitz said. “Some people say getting accepted is actually harder than school itself.”

When he received his acceptance letter for vet school, the doctor at the eye clinic let him take on more skilled tasks, like intubating pets who were about to undergo surgery.

“I really enjoyed being able to do all that, and I am excited to continue to develop more skills at school,” Manglitz said.

His first year of classes concluded with a multi-day field trip to the Great Plains Veterinary Education Center in Clay Center, Nebraska. The trip, fondly known as “Cow Camp,” teaches the students about examining and treating large animals, like cattle or swine. It also showed Manglitz that even domestic veterinary medicine can involve exotic experiences.

“At the end, we did a full exam on a heifer that required a rectal palpation, meaning you stick your hand in to feel for its uterus and ovaries as a pregnancy test,” he said. “It was kind of weird to be elbow deep in a cow, but a really unique experience.”